Difference between revisions of "The Data Processing Inequality"

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

& = H\left(Y\right) + H\left(X \mid Y\right) \\ | & = H\left(Y\right) + H\left(X \mid Y\right) \\ | ||

& = H\left(Y, X\right) | & = H\left(Y, X\right) | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|1}}}} |

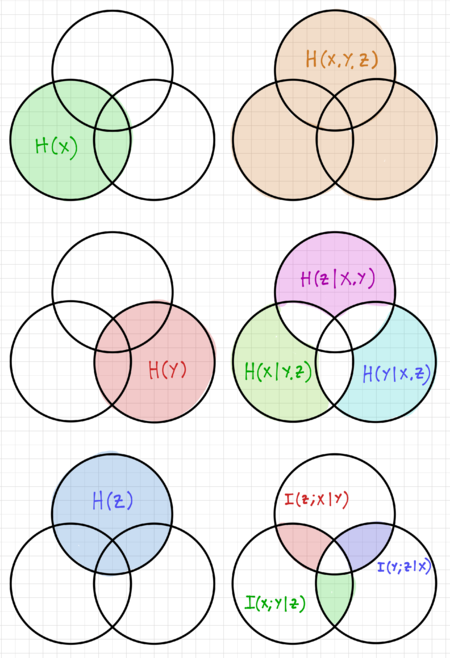

We can use Venn diagrams to visualize these relationships, as seen in Fig. 1. For three random variables <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math>, and <math>Z</math>: | We can use Venn diagrams to visualize these relationships, as seen in Fig. 1. For three random variables <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math>, and <math>Z</math>: | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

H\left(X, Y, Z\right) & = H\left(X\right) + H\left(Y, Z\mid X\right) \\ | H\left(X, Y, Z\right) & = H\left(X\right) + H\left(Y, Z\mid X\right) \\ | ||

& = H\left(X\right) + H\left(Y \mid X\right) + H\left(Z \mid Y, X\right)\\ | & = H\left(X\right) + H\left(Y \mid X\right) + H\left(Z \mid Y, X\right)\\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|2}}}} |

In general: | In general: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>H\left(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n H\left(X_i \mid X_{i-1}, X_{i-2},\ldots, X_1\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>H\left(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n H\left(X_i \mid X_{i-1}, X_{i-2},\ldots, X_1\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|3}}}} |

== Conditional Mutual Information == | == Conditional Mutual Information == | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

I\left(X;Y\mid Z\right) & = \sum_{z\in Z} P\left(z\right) \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x,y\mid z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(x,y\mid z\right)}{P\left(x\mid z\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid z\right)} \\ | I\left(X;Y\mid Z\right) & = \sum_{z\in Z} P\left(z\right) \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x,y\mid z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(x,y\mid z\right)}{P\left(x\mid z\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid z\right)} \\ | ||

& = \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot\log_2 \frac{P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot P\left(z\right)}{P\left(x, z\right)\cdot P\left(y, z\right)} \\ | & = \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot\log_2 \frac{P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot P\left(z\right)}{P\left(x, z\right)\cdot P\left(y, z\right)} \\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|4}}}} |

We can rewrite the definition of conditional mutual information as: | We can rewrite the definition of conditional mutual information as: | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

& = \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(z\right)}{P\left(x, z\right)} - \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(y, z\right)}{P\left(x, y, z\right)} \\ | & = \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(z\right)}{P\left(x, z\right)} - \sum_{z\in Z} \sum_{y\in Y} \sum_{x\in X} P\left(x, y, z\right)\cdot \log_2\frac{P\left(y, z\right)}{P\left(x, y, z\right)} \\ | ||

& = H\left(X\mid Z\right) - H\left(X\mid Y, Z\right)\\ | & = H\left(X\mid Z\right) - H\left(X\mid Y, Z\right)\\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|5}}}} |

[[File:Entropy xyz venn.png|thumb|450px|Figure 2: Entropy visualization for three random variables using Venn diagrams.]] | [[File:Entropy xyz venn.png|thumb|450px|Figure 2: Entropy visualization for three random variables using Venn diagrams.]] | ||

We can visualize this relationship using the Venn diagrams in Fig. 2. Compare this to our expression for the mutual information of two random variables <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math>: | We can visualize this relationship using the Venn diagrams in Fig. 2. Compare this to our expression for the mutual information of two random variables <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math>: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Y\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Y\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|6}}}} |

=== Chain Rule for Mutual Information === | === Chain Rule for Mutual Information === | ||

For random variables <math>X</math> and <math>Z</math>: | For random variables <math>X</math> and <math>Z</math>: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Z\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Z\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|7}}}} |

And for random variables <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math> and <math>Z</math>: | And for random variables <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math> and <math>Z</math>: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y,Z\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Y,Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y,Z\right) = H\left(X\right) - H\left(X\mid Y,Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|8}}}} |

We can then express the conditional mutual information as: | We can then express the conditional mutual information as: | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

& = H\left(X\right) - I\left(X;Z\right) + I\left(X;Y,Z\right) - H\left(X\right) \\ | & = H\left(X\right) - I\left(X;Z\right) + I\left(X;Y,Z\right) - H\left(X\right) \\ | ||

& = I\left(X;Y,Z\right) - I\left(X;Z\right) \\ | & = I\left(X;Y,Z\right) - I\left(X;Z\right) \\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|9}}}} |

Rearranging, we then obtain the chain rule for mutual information: | Rearranging, we then obtain the chain rule for mutual information: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y,Z\right) = I\left(X;Y\mid Z\right) + I\left(X;Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(X;Y,Z\right) = I\left(X;Y\mid Z\right) + I\left(X;Z\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|10}}}} |

Thus, we can extend this for additional random variables: | Thus, we can extend this for additional random variables: | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

I\left(Y;X_1,X_2,X_3\right) & = I\left(Y;X_3\mid X_2,X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_2,X_1\right) \\ | I\left(Y;X_1,X_2,X_3\right) & = I\left(Y;X_3\mid X_2,X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_2,X_1\right) \\ | ||

& = I\left(Y;X_3\mid X_2,X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_2\mid X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_1\right)\\ | & = I\left(Y;X_3\mid X_2,X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_2\mid X_1\right) + I\left(Y;X_1\right)\\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|11}}}} |

In general: | In general: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(Y;X_1, X_2,\ldots ,X_n\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n I\left(Y;X_i\mid X_{i-1}, X_{i-2},\dots ,X_1\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>I\left(Y;X_1, X_2,\ldots ,X_n\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n I\left(Y;X_i\mid X_{i-1}, X_{i-2},\dots ,X_1\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|12}}}} |

== Markovity == | == Markovity == | ||

A [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markov_chain Markov Chain] is a random process that describes a sequence of possible events where the probability of each event depends only on the outcome of the previous event. Thus, we say that <math>X, Y, Z</math> is a Markov chain in this order, denoted as: | A [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markov_chain Markov Chain] is a random process that describes a sequence of possible events where the probability of each event depends only on the outcome of the previous event. Thus, we say that <math>X, Y, Z</math> is a Markov chain in this order, denoted as: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>|{{EquationRef|13}}}} |

If we can write: | If we can write: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(X=x, Y=y, Z=z\right) = P\left(Z=z\mid Y=y\right)\cdot P\left(Y=y\mid X=x\right) \cdot P\left(X=x\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(X=x, Y=y, Z=z\right) = P\left(Z=z\mid Y=y\right)\cdot P\left(Y=y\mid X=x\right) \cdot P\left(X=x\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|14}}}} |

Or in a more compact form: | Or in a more compact form: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, y, z\right) = P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid x\right) \cdot P\left(x\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, y, z\right) = P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid x\right) \cdot P\left(x\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|15}}}} |

We can use Markov chains to model how a signal is corrupted when passed through noisy channels. For example, if <math>X</math> is a binary signal, it can change with a certain probability, <math>p</math>, to <math>Y</math>, and it can again be corrupted to produce <math>Z</math>. | We can use Markov chains to model how a signal is corrupted when passed through noisy channels. For example, if <math>X</math> is a binary signal, it can change with a certain probability, <math>p</math>, to <math>Y</math>, and it can again be corrupted to produce <math>Z</math>. | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

Consider the joint probability <math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right)</math>. We can express this as: | Consider the joint probability <math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right)</math>. We can express this as: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(x, y, z\right)}{P\left(y\right)}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(x, y, z\right)}{P\left(y\right)}</math>|{{EquationRef|16}}}} |

And if <math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>, we get: | And if <math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>, we get: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid x\right) \cdot P\left(x\right)}{P\left(y\right)}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\mid x\right) \cdot P\left(x\right)}{P\left(y\right)}</math>|{{EquationRef|17}}}} |

Since <math>P\left(y,x\right)=P\left(y\mid x\right)\cdot P\left(x\right) = P\left(x\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\right)</math>, we can write: | Since <math>P\left(y,x\right)=P\left(y\mid x\right)\cdot P\left(x\right) = P\left(x\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y\right)</math>, we can write: | ||

| − | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y, x\right)}{P\left(y\right)}=P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(x\mid y\right)</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P\left(x, z\mid y\right) = \frac{P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(y, x\right)}{P\left(y\right)}=P\left(z\mid y\right)\cdot P\left(x\mid y\right)</math>|{{EquationRef|18}}}} |

Thus, we can say that <math>X</math> and <math>Z</math> are conditionally independent given <math>Y</math>. If we think of <math>X</math> as some past event, and <math>Z</math> as some future event, then the past and future events are independent if we know the present event <math>Y</math>. Note that this property is good definition of, as well as a useful tool for checking Markovity. | Thus, we can say that <math>X</math> and <math>Z</math> are conditionally independent given <math>Y</math>. If we think of <math>X</math> as some past event, and <math>Z</math> as some future event, then the past and future events are independent if we know the present event <math>Y</math>. Note that this property is good definition of, as well as a useful tool for checking Markovity. | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

& = P\left(z, y\right)\cdot P\left(x\mid y\right)\\ | & = P\left(z, y\right)\cdot P\left(x\mid y\right)\\ | ||

& = P\left(x\mid y\right) \cdot P\left(y\mid z\right) \cdot P\left(z\right)\\ | & = P\left(x\mid y\right) \cdot P\left(y\mid z\right) \cdot P\left(z\right)\\ | ||

| − | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef| | + | \end{align}</math>|{{EquationRef|19}}}} |

Therefore, if <math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>, then it follows that <math>Z \rightarrow Y \rightarrow X</math>. | Therefore, if <math>X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z</math>, then it follows that <math>Z \rightarrow Y \rightarrow X</math>. | ||

Revision as of 15:34, 28 October 2020

Contents

Entropy Chain Rules

As we increase the number of random variables we are dealing with, it is important to understand how this increase affects entropy. We have previously shown that for two random variables and :

-

(1)

-

We can use Venn diagrams to visualize these relationships, as seen in Fig. 1. For three random variables , , and :

-

(2)

-

In general:

-

(3)

-

Conditional Mutual Information

Conditional mutual information is defined as the expected value of the mutual information of two random variables given the value of a third random variable, and for three random variables , , and , it is defined as:

-

(4)

-

We can rewrite the definition of conditional mutual information as:

-

(5)

-

We can visualize this relationship using the Venn diagrams in Fig. 2. Compare this to our expression for the mutual information of two random variables and :

-

(6)

-

Chain Rule for Mutual Information

For random variables and :

-

(7)

-

And for random variables , and :

-

(8)

-

We can then express the conditional mutual information as:

-

(9)

-

Rearranging, we then obtain the chain rule for mutual information:

-

(10)

-

Thus, we can extend this for additional random variables:

-

(11)

-

In general:

-

(12)

-

Markovity

A Markov Chain is a random process that describes a sequence of possible events where the probability of each event depends only on the outcome of the previous event. Thus, we say that is a Markov chain in this order, denoted as:

-

(13)

-

If we can write:

-

(14)

-

Or in a more compact form:

-

(15)

-

We can use Markov chains to model how a signal is corrupted when passed through noisy channels. For example, if is a binary signal, it can change with a certain probability, , to , and it can again be corrupted to produce .

Consider the joint probability . We can express this as:

-

(16)

-

And if , we get:

-

(17)

-

Since , we can write:

-

(18)

-

Thus, we can say that and are conditionally independent given . If we think of as some past event, and as some future event, then the past and future events are independent if we know the present event . Note that this property is good definition of, as well as a useful tool for checking Markovity.

We can rewrite the joint probability as:

-

(19)

-

Therefore, if , then it follows that .

The Data Processing Inequality

Consider three random variables, , , and . The mutual information can be expressed as:

-

(20)

-

If , i.e. , , and form a Markov chain, then is conditionally independent of given , resulting in . Thus,

-

(21)

-

And since , we get:

-

(21)

-