Difference between revisions of "Noise in RF Circuits"

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{{NumBlk|::|<math>P_n = \lim_{T\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T n^2\left(t\right) dt</math>|{{EquationRef|1}}}} | {{NumBlk|::|<math>P_n = \lim_{T\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T n^2\left(t\right) dt</math>|{{EquationRef|1}}}} | ||

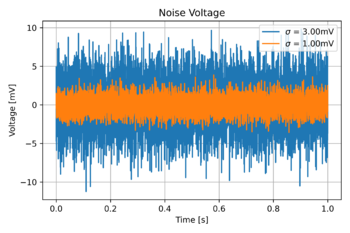

| − | [[File:Noise transient 1.png|thumb| | + | [[File:Noise transient 1.png|thumb|350px|Figure 2: Zero-mean noise signals in time with different variances.]] |

Thus, to describe noise, we can use its variance, or equivalently its average power. Fig. 2 illustrates the difference between two noise signals with different variances. Recall that <math>\sigma</math>, the square root of the variance, is the standard deviation. | Thus, to describe noise, we can use its variance, or equivalently its average power. Fig. 2 illustrates the difference between two noise signals with different variances. Recall that <math>\sigma</math>, the square root of the variance, is the standard deviation. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

{{NumBlk|::|<math>v_{n,\mathrm{rms}}=\sqrt{\overline{v^2_n}} = \sqrt{\lim_{T\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T v^2_n\!\left(t\right) dt}</math>|{{EquationRef|3}}}} | {{NumBlk|::|<math>v_{n,\mathrm{rms}}=\sqrt{\overline{v^2_n}} = \sqrt{\lim_{T\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T v^2_n\!\left(t\right) dt}</math>|{{EquationRef|3}}}} | ||

| − | == Noise Spectrum == | + | == Noise Power Spectrum == |

| − | We can also examine the noise in the frequency domain. | + | We can also examine the noise in the frequency domain, specifically, how noise power is distributed over frequency. |

== Noise Shaping == | == Noise Shaping == | ||

Revision as of 09:47, 4 October 2020

In this module, we consider the noise generated by the electronic devices themselves due to the (1) random motion of electrons due to thermal energy and (2) the discreteness of electric charge. We see this as thermal noise in resistances, and shot noise in PN junctions. In MOS transistors, we also see flicker noise. This noise is not fundamental, but is due to the way MOS transistors are manufactured, This added uncertainty in the voltages and currents limit the smallest signal amplitude or power that our circuits can detect and/or process, limiting the transmission range and power requirements for reliable communications.

Contents

Modeling Noise

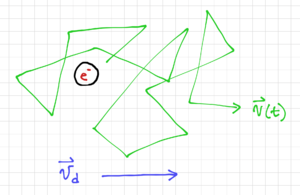

Since electronic noise is random, we cannot predict its value at any given time. However, we can describe noise in terms of its aggregate characteristics or statistics, such as its probability distribution function (pdf). As expected from the Central Limit Theorem, the pdf of the random movement of many electrons would approach a Gaussian distribution with zero mean since the electrons will move around instantaneously, but without any excitation, it will, on the average, stay in the same point in space. If we add an electric field, then the electron will move with an average drift velocity, , but at any point in time, it would be moving with an instantaneous velocity , as shown in Fig. 1. Note that is the electron mobility.

Noise Power

Aside from the mean, to describe a zero-mean Gaussian random variable, , we need the variance, , or the mean of . For random voltages or currents, , this is equal to the average power over time, normalized to :

-

(1)

-

Thus, to describe noise, we can use its variance, or equivalently its average power. Fig. 2 illustrates the difference between two noise signals with different variances. Recall that , the square root of the variance, is the standard deviation.

Consider a noise voltage in time, . The mean is then:

-

(2)

-

The variance, however, is non-zero:

-

(2)

-

We can also calculate the root-mean-square or RMS as:

-

(3)

-

Noise Power Spectrum

We can also examine the noise in the frequency domain, specifically, how noise power is distributed over frequency.